Framing the Literacy Crisis

Literacy is a cornerstone of justice, equity, and opportunity, yet across the United States, millions of students are falling short of literacy benchmarks. According to the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP), 65% of fourth graders and 66% of eighth graders in the United States are reading below proficiency levels. These statistics are even more alarming for students from marginalized communities, where systemic inequities compound barriers to literacy development (NAEP, 2022). Black and Hispanic students, students from low-income families, and multilingual learners are disproportionately represented among those struggling to meet literacy standards.

Literacy, therefore, is not merely an academic concern—it is a social justice imperative.

– Gholdy Muhammad

Beyond the academic realm, low literacy rates perpetuate cycles of poverty and limit social mobility. Adults with low literacy levels are more likely to face unemployment, earn lower wages, and experience incarceration.

While the data is sobering, it also illuminates the extraordinary potential we unlock when students experience the joy of reading, the pride of authorship, and the empowerment of seeing themselves reflected in meaningful and inspiring stories.

The Call for Critical Literacy

To address these challenges, we must move beyond traditional literacy instruction and embrace a vision of critical literacy—one that equips learners with the ability to engage analytically and critically with texts, questioning the social, institutional, and ideological aspects embedded within them (Ibrahim, 2023).

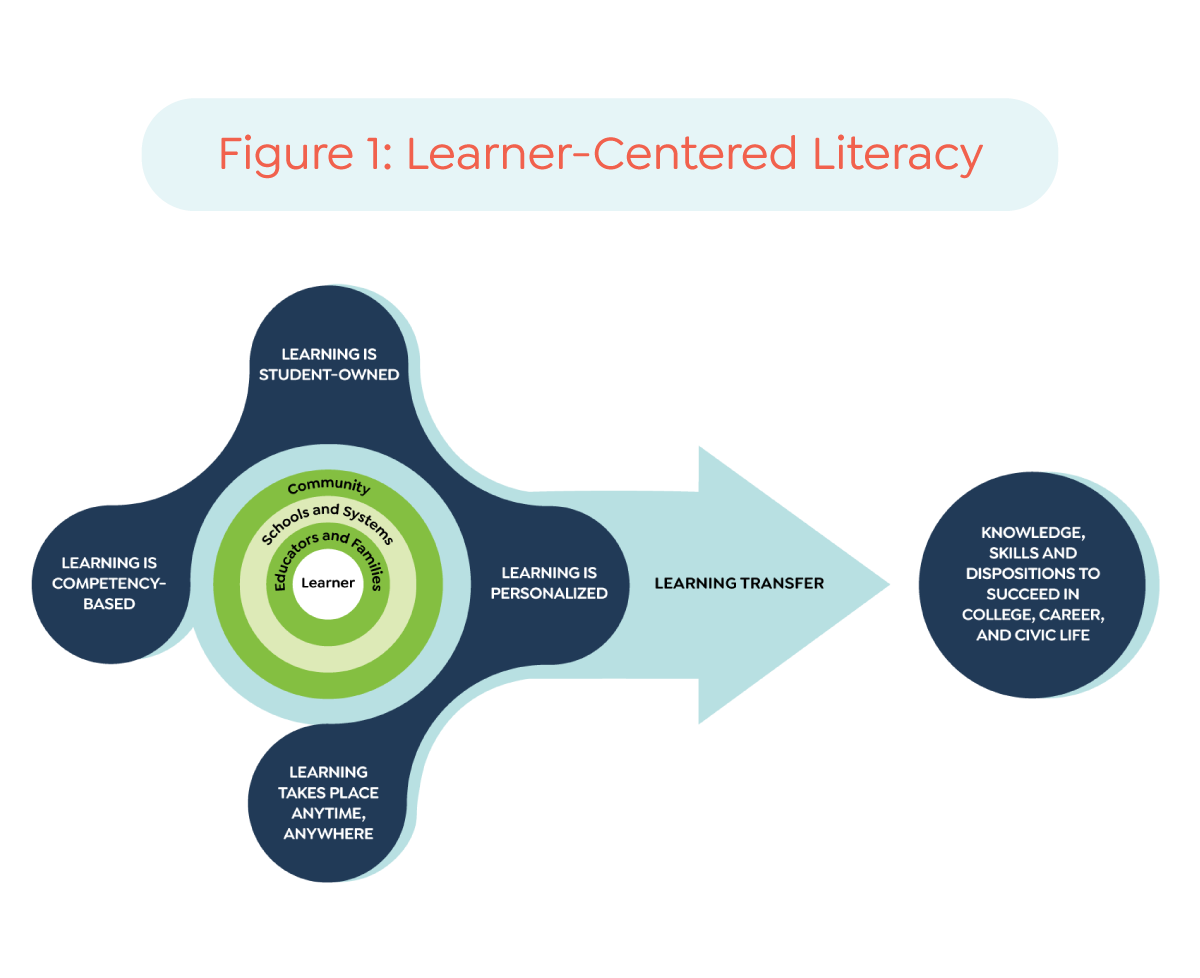

We begin with learner-centered literacy— placing students at the heart of reading, writing, speaking, and listening. As seen in Figure 1 below, learner-centered literacy ensures that:

- Learning is competency-based – Students progress based on demonstrated mastery, not seat time.

- Learning is student-owned – Learners take agency over their goals, strategies, and reflection.

- Learning is personalized – Instruction is responsive to students’ identities, strengths, and needs.

- Learning happens anytime, anywhere – Literacy development is no longer confined to classroom walls or rigid schedules.

This flexible framing of learning moves beyond what the teacher is doing to how students engage in the learning process.

Our learner-centered literacy approach is grounded in the Active View of Reading model, which positions readers as active constructors of meaning rather than passive recipients of information (Rumelhart, 1980; RAND Reading Study Group, 2002). This model recognizes that comprehension occurs through dynamic interaction between the reader, text, and context, validating the cultural knowledge, experiences, and perspectives that all students bring to literacy learning (García & Wei, 2014). By understanding reading as an active, strategic process of meaning construction, students develop the metacognitive awareness essential for questioning texts, examining bias, and challenging inequitable narratives. The Active View provides a foundation for critical literacy by empowering students to see themselves as metacognitive meaning-makers capable of engaging with texts strategically and with an analytical eye.

Critical literacy is more essential than ever. Social media, cable news programming, and independently owned media have made information more vulnerable to bias, inaccuracy, and manipulation. The rise of artificial intelligence further complicates the way information is generated, requiring readers to assess authenticity and credibility across multiple formats, from print to digital, video, and images.

The Neuroscience of Critical Literacy

Brain research reveals how critical literacy skills develop and can be strengthened through intentional instruction.

- Reading comprehension activates multiple brain networks

Neuroimaging studies show that critical analysis engages executive function areas beyond basic decoding regions (Cutting et al., 2013). - Metacognitive awareness strengthens neural pathways

Students who reflect on their thinking show increased connectivity between prefrontal and posterior brain regions (Zelazo et al., 2003). - Vocabulary depth impacts comprehension networks

Rich vocabulary instruction creates stronger neural connections that support critical text analysis (Perfetti & Stafura, 2014). - Social cognition enhances perspective-taking

Brain regions involved in understanding others’ viewpoints are activated during critical literacy tasks (Schurz et al., 2014). - Deliberate practice creates lasting changes

Repeated engagement with critical thinking tasks strengthens neural efficiency and automaticity (Dunlosky et al., 2013).

As Vasquez (2017) notes, critical literacy is particularly relevant in diverse classrooms, where students encounter a range of texts that demand critical engagement. The ability to quickly determine importance and relevance, recognize bias, and synthesize information from multiple sources has become a fundamental literacy skill. Nonfiction itself must be redefined—not as “real” but as information, ideas, and opinions about the real world, all of which require critical examination. Kellner and Share (2005) argue that critical media literacy is essential for fostering an informed citizenry capable of participating in democratic processes. Without these skills, students risk becoming passive consumers of information rather than active, engaged learners.

Critical literacy also involves understanding how language and information shape beliefs, identities, and societal structures, encouraging learners to challenge inequities and advocate for social justice (Muhammad, 2020). Importantly, critical thinking is not merely a skill set but a process of acquiring deep knowledge about all sides of an issue before evaluating diverse perspectives and developing an informed opinion. It is about intellectual depth—moving beyond surface-level analysis to interrogate power, perspective, and truth.

Being Assessment Capable Supports Critical Literacy

Our ultimate goal is to cultivate students who are not only proficient readers and writers but also have agency and are assessment-capable learners (Wiliam, 2011). An assessment-capable learner actively engages in their learning process, understands their progress, and takes ownership through self-assessment, goal setting, and reflection. These practices foster self-awareness, ownership, and the critical thinking skills essential for critical literacy and lifelong success.

The transformation toward critical literacy requires intentionality, systemic change, and a commitment to justice. The Core Collaborative Learning Network proposes a framework grounded in seven tenets of literacy: phonemic awareness, phonics, vocabulary, fluency, comprehension, academic discourse, and evidence-based writing instruction. These tenets are not isolated skills but interconnected components of a literacy program designed to foster critical thinking, agency, and equity. By embedding critical literacy within this framework, we ensure that students are not only learning to read and write but also developing the tools to navigate an increasingly complex world with confidence, discernment, and purpose.

Building Blocks of Critical Literacy

Critical literacy empowers students to engage deeply with texts, analyze diverse perspectives, and take meaningful action in the world. Grounded in essential competencies, it develops skills that enable students to decode, comprehend, and critique information while fostering communication and advocacy. These building blocks prioritize equity and inclusivity, ensuring all students are equipped to navigate complex ideas and contribute their voices to the conversation.

01 Phonemic Awareness

Foundational literacy begins with the ability to hear, identify, and manipulate phonemes, the smallest units of sound within words. Phonemic awareness is the gateway to decoding, enabling students to break the code of written language. Without this skill, students face insurmountable barriers to fluency and comprehension and with it they have markedly better life prospects. Effective programs embed phonemic awareness in engaging, culturally responsive activities that honor students’ linguistic backgrounds. The National Reading Panel emphasizes that explicit instruction in phonemic awareness can significantly enhance children’s reading abilities, particularly in early education settings (Khor et al., 2014).

02 Phonics

Systematic phonics instruction bridges the gap between phonemic awareness and reading fluency. Evidence-based approaches ensure that students learn the sound-symbol relationships essential for decoding words. Equity-focused phonics instruction includes materials that reflect diverse cultures and languages, making learning meaningful and accessible for all students. Studies have shown that systematic phonics instruction leads to better reading outcomes compared to non-systematic or no phonics instruction (Verhoeven & Leeuwe, 2011).

03 Vocabulary

Vocabulary development is essential for comprehension and critical analysis. Students with limited vocabulary are at a disadvantage in accessing complex texts and engaging in academic discourse. Vocabulary instruction must go beyond rote memorization to include opportunities for rich, contextual learning and exploration of words across disciplines. The National Reading Panel asserts that vocabulary instruction should be explicit and integrated into reading activities to maximize its impact on comprehension (Westby, 2018).

04 Fluency

Fluency is the bridge between decoding and comprehension. Students must read with accuracy, appropriate speed, and expression to understand and engage with text. Deliberate practice—including repeated readings, performance tasks, and peer feedback—builds fluency and fosters confidence. The National Reading Panel highlights that fluency is not merely about speed; it also encompasses prosody, or the rhythm and intonation of speech (Kühn et al., 2010).

05 Comprehension

Comprehension is the heart of critical literacy. It involves not just understanding what a text says but also analyzing its purpose, biases, and implications.

Instruction should include authentic texts, opportunities for dialogue, and tasks that encourage students to connect their learning to real-world issues. Assessment for learning practices—such as student self-assessment and peer review—support deeper comprehension. The National Reading Panel emphasizes that comprehension strategies, such as summarization and questioning, should be explicitly taught to improve students’ understanding of what they read (Khor et al., 2014).

06 Academic Discourse

Academic Discourse is the foundation of collaborative and critical learning. It encompasses the structured exchange of ideas through speaking, listening, and writing in formal and informal settings. Effective academic discourse develops students’ ability to articulate their thoughts, engage in respectful dialogue, and analyze diverse perspectives. Moon et al. argue that “for classroom talk to be effective, the instructor must explicitly scaffold the development of skills necessary for successful discourse” (Moon et al., 2017). This scaffolding is essential in helping students navigate complex discussions and ensuring that all voices are heard, particularly in diverse classrooms where students may have varying levels of proficiency in academic language.

07 Evidence-Based Writing Instruction

Evidence-Based Writing Instruction is essential to effective communication, reflection, and advocacy. Evidence-based writing instruction develops students’ ability to construct arguments, provide evidence, and express ideas clearly and persuasively. Writing tasks should be rooted in students’ lived experiences and tied to meaningful, real-world purposes (Peachey, 2023). “An important component of critical literacy is the role of student agency to write about and advocate for the topics that they care the most about” (Flint, 2022). This quote underscores the significance of empowering students to take ownership of their writing, which is crucial for developing their critical thinking and engagement with societal issues.

A Special Note Regarding Phonemic Awareness and Equity

Research shows that culturally responsive phonemic awareness instruction benefits all students, particularly multilingual learners.

- Multilingual students transfer phonemic skills

Students can apply phonemic awareness across languages, accelerating English literacy development (Bialystok, 2007). - Culturally relevant materials increase engagement

Phonemic awareness activities using students’ cultural references show higher participation rates (August & Shanahan, 2006). - Explicit instruction benefits all learners

Systematic phonemic awareness instruction particularly helps students from low-income backgrounds (Ehri et al., 2001). - Music and movement enhance learning

Phonemic awareness activities incorporating rhythm and song improve retention for diverse learners (Bolduc, 2009).

Assessment for Learning

A Pathway to Critical Literacy

Critical literacy empowers students to engage deeply with texts, question bias, and navigate complex information landscapes. However, becoming informed and engaged citizens requires more than exposure to diverse texts—it demands intentional support for how students process, evaluate, and apply what they learn. This is where Assessment for Learning (AfL) plays a crucial role.

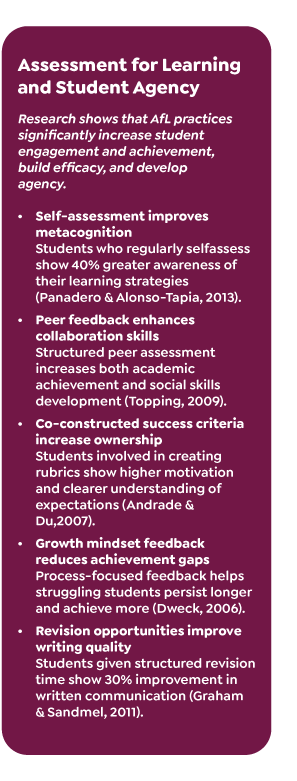

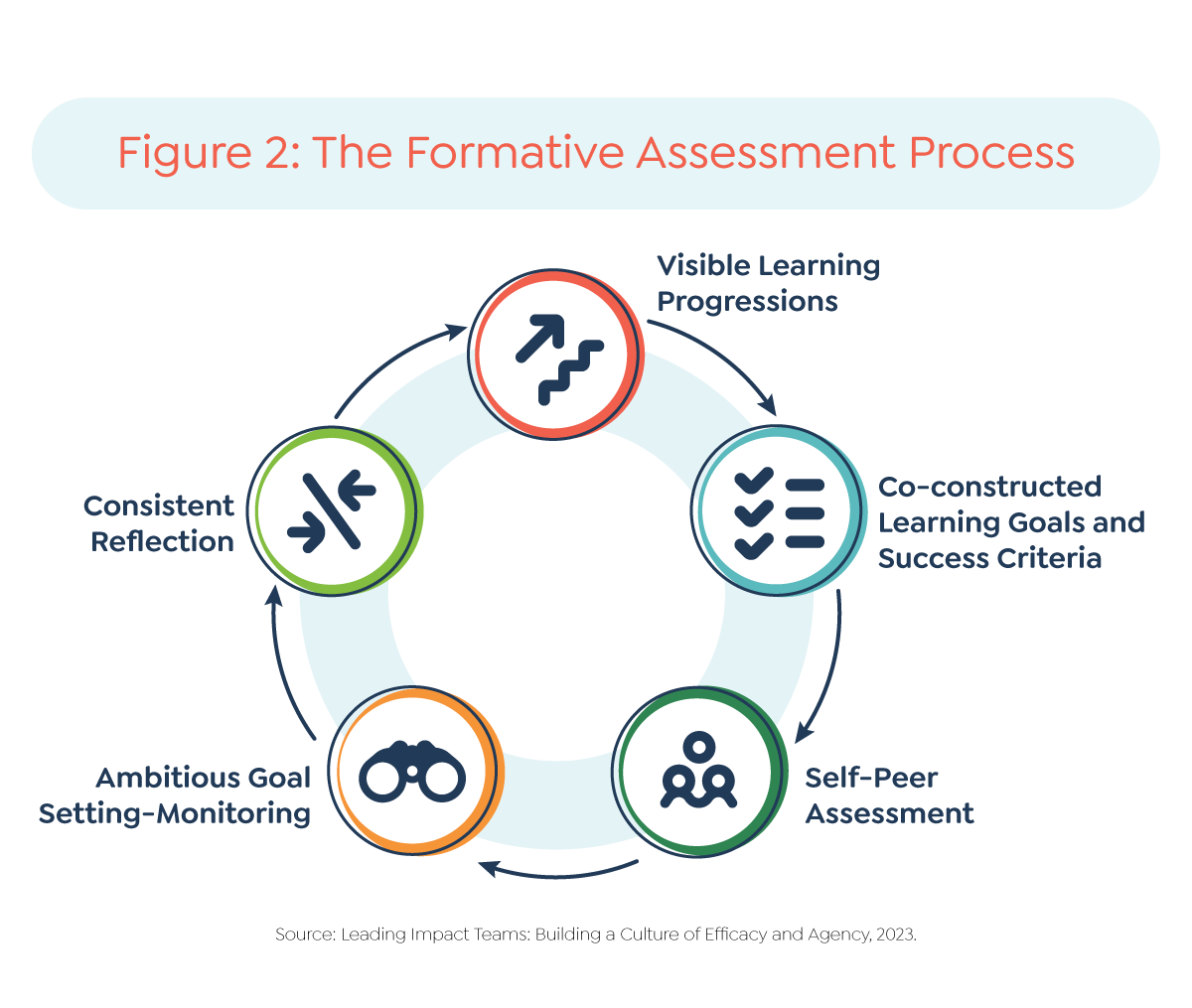

AfL is an ongoing process in which teachers and students use formative assessment strategies—self- and peer assessment, goal setting, reflection, co-constructing success criteria, and checks for understanding—to gather, interpret, and act on evidence of learning. Much like critical literacy, AfL fosters reflection, self-regulation, and continuous growth, ensuring students take an active role in their learning. Sari and Saadah (2022) highlight the essential role of formative assessment in shaping learning, while Nicol and Macfarlane-Dick (2006) emphasize its power to empower students as self-regulated learners by generating feedback that accelerates progress.

By integrating AfL, educators create an environment in which students not only acquire knowledge but also develop the metacognitive skills needed to think critically and take ownership of their learning. AfL supports agency, reflection, and critical thinking—the same qualities critical literacy cultivates—preparing students to navigate complex information with confidence.

Moreover, AfL fosters belonging and self-efficacy, key drivers of student motivation (Shepard et al., 2018). By shifting the focus from grades to the learning process, it nurtures resilience, encouraging students to see challenges as opportunities rather than obstacles. In this way, AfL and critical literacy work together to develop students who question, analyze, and engage meaningfully with the world, fostering a lifelong commitment to learning and informed civic participation.

Why is AfL Essential for Critical Literacy?

Critical literacy empowers students to engage deeply with texts, analyze diverse perspectives, and take meaningful action in the world. Grounded in essential competencies, it develops skills that enable students to decode, comprehend, and critique information while fostering communication and advocacy. These tenets prioritize equity and inclusivity, ensuring all students are equipped to navigate complex ideas and contribute their voices to the conversation.

01 Fosters Metacognition and Self-Regulation

- Critical literacy requires students to question texts, analyze power structures, and interpret meaning through a reflective lens. These skills thrive when students are trained to monitor and regulate their thinking.

- AfL encourages students to reflect on their learning process, identify their strengths, and recognize areas for growth.

02 Encourages Learner Agency

- Critical literacy depends on students’ ability to take ownership of their perspectives and advocate for social justice, which stems from the confidence built through active participation in assessment.

- By involving students in self- and peer assessment, AfL places them at the center of their learning journey.

03 Supports Mastery of Complex Skills

- Critical literacy involves nuanced skills like analyzing diverse perspectives, evaluating biases, and synthesizing multiple sources of information.

- AfL provides timely, actionable feedback that supports students in mastering these complex skills incrementally.

04 Builds Resilience and Openness to Challenge

- Critical literacy demands that students confront uncomfortable truths and revise their thinking. This process nurtures dispositions such as perseverance, adaptability, and a willingness to engage with complexity—all essential for critical inquiry and social awareness.

- AfL emphasizes progress over perfection by centering formative feedback rather than summative judgment, reinforcing the idea that learning is an evolving process shaped by effort, reflection, and revision.

05 Promotes Equity

- Critical literacy inherently aims to dismantle inequities, and AfL ensures all students have the opportunity to engage meaningfully, regardless of their starting point.

- AfL aligns with culturally responsive teaching practices, ensuring that assessments honor diverse ways of knowing and communicating.

06 Integrates Critical Questioning

- Critical literacy is not possible without students learning to practice critical questioning.

- AfL involves the co-construction of success criteria, which can embed critical literacy practices like questioning authorship, purpose, and perspective.

07 Builds Collaborative Skills

- Critical literacy thrives in collaborative settings where students interrogate ideas and challenge assumptions together.

- Peer assessment in AfL fosters collaboration, dialogue, and shared meaning-making.

08 Connects Learning to Real-World Contexts

- Critical literacy helps students see how their learning connects to broader societal issues and equips them to take informed action.

- AfL encourages the application of knowledge to authentic contexts, which is crucial for critical literacy.

Unlike traditional assessments that merely measure outcomes, assessment for learning involves ongoing, formative practices that guide instruction and support student growth. By focusing on progress, reflection, and meaningful feedback, assessment for learning creates a foundation for students to develop the critical thinking, self-awareness, and active engagement necessary for critical literacy. It aligns learning with equity and agency, preparing students to navigate and challenge the complexities of the world.

AfL Strategies to Build Critical Literacy Skills

AfL strategies such as co-constructing learning intentions, self-assessment, peer feedback, and reflection empower students to take charge of their learning and foster the skills necessary for critical literacy (Wiliam, 2011). John Hattie’s research highlights the power of assessment for learning, with an effect size of 0.75—far above the threshold of 0.4, which represents a year’s worth of growth in a year’s time (Hattie, 2009). This evidence underscores that when students are actively involved in the assessment process, their engagement and learning outcomes significantly improve.

Fostering agency in students means giving them the tools and confidence to take charge of their learning.

Assessment for Learning is achieved through intentional practices such as:

Learning Intentions and Success Criteria

Begin by co-constructing learning intentions and success criteria with students to ensure clarity and shared understanding of what success looks like. This process promotes equity by valuing diverse perspectives and making the learning journey transparent for all students.

Self-Assessment

Encouraging students to evaluate their own work against clear success criteria helps them identify strengths and areas for improvement. Self-assessment promotes metacognition and accountability. Guskey asserts, “Effective self-assessment requires a clear understanding of the criteria for success” (Earley & Porritt, 2013).

Peer Assessment

Structured opportunities for students to provide constructive feedback to their peers not only enhance learning but also build collaboration and critical thinking skills.

Goal Setting

Guiding students to set meaningful, achievable goals tied to their learning helps them focus their efforts and measure progress.

Reflection

Creating time for students to reflect on their learning experiences fosters deeper understanding and resilience. Reflection also reinforces the connection between effort, strategy, and outcomes.

Revision

Building in opportunities for students to revise their work based on feedback and self-reflection underscores the value of growth and learning from mistakes. Revision ensures all students have access to achieving high standards by promoting persistence and celebrating progress over perfection.

Embedding co-construction into learning intentions, success criteria, and assessment practices elevates equity by creating a shared sense of purpose and opportunity. This iterative cycle of self-assessment, peer feedback, reflection, and revision builds the critical skills and dispositions needed for lifelong learning.

Embedding co-construction into learning intentions, success criteria, and assessment practices elevates equity by creating a shared sense of purpose and opportunity. This iterative cycle of self-assessment, peer feedback, reflection, and revision builds the critical skills and dispositions needed for lifelong learning.

Creating a Critical Literacy Ecosystem

The transformation to critical literacy is not the work of individual teachers or students alone. It requires collective efficacy—the shared belief that, together, we can achieve extraordinary outcomes. Critical literacy is a theoretical and practical framework that can readily take on such challenges, creating spaces for literacy work that can contribute to creating a more critically informed and just world” (Vasquez, 2017). This idea illustrates the broader implications of critical literacy, suggesting that it not only benefits individual learners but also contributes to social justice and equity through informed engagement with texts. Ladson-Billings’ work (2014) highlights the necessity of integrating critical literacy into the curriculum to address the historical and ongoing marginalization of certain groups. She emphasizes that educators must confront the “educational debt” that has accumulated over generations due to systemic inequities, which she describes as “the historical, economic, and cultural debts that have been accrued through the marginalization of students of color” (Means & Taylor, 2010). By acknowledging this debt, educators can better understand the importance of critical literacy as a tool for social justice and equity in education.

Deliberate practice—focused, goal-oriented, reflective, and iterative—is the engine of critical literacy growth. Students need ample opportunities to practice reading, writing, and critical thinking in supportive environments where mistakes are seen as opportunities to learn. Educators, in turn, need professional learning experiences that deepen their expertise and provide actionable strategies for fostering literacy development. When educators collaborate to analyze data, design interventions, and reflect on deliberate practice opportunities, they create a culture of continuous improvement that benefits all students.

Belonging is another essential theme. Students must see themselves reflected in the curriculum and feel valued as members of the learning community. Culturally responsive teaching practices, inclusive materials, and opportunities for student voice ensure that every learner feels a sense of ownership of and agency over their learning.

The Core Collaborative Solution

At the heart of education lies the transformative power of literacy—a pathway to equity, empowerment, and opportunity. Yet, across the United States, far too many students, especially those from historically marginalized communities, face significant barriers to achieving literacy proficiency. Literacy is not just an academic skill; it is a social justice imperative that shapes the future of individuals, families, and entire communities. To address this urgent need, we offer a comprehensive suite of learner-centered services designed to reimagine literacy programs through the lens of critical literacy. Grounded in research and equity-focused practices, these services go beyond traditional instruction, empowering students to think critically, challenge inequities, and take action for meaningful change. By centering culturally responsive teaching, student agency, and assessment for learning, we equip educators, leaders, and communities with the tools to create inclusive, empowering, and justicedriven learning environments. Let’s build a personalized approach to fit your needs, pulling from the following offerings:

Critical Literacy Professional Development for Educators

- Workshops and training on integrating critical literacy into instruction.

- Strategies for fostering agency, critical thinking, and equity in literacy classrooms.

- Culturally responsive teaching practices for diverse learners.

Assessment for Learning (AfL) Framework Implementation

- Training educators on formative assessment strategies.

- Tools for co-constructing success criteria, self-assessment, and peer feedback.

- Embedding reflection and revision opportunities to support mastery of complex skills.

Curriculum Design and Auditing

- Development of culturally relevant and equity-focused literacy programs.

- Alignment of curriculum with the seven tenets of literacy.

- Incorporating authentic texts and materials reflecting diverse cultures.

Critical Literacy Coaching

- Ongoing coaching for teachers to embed critical literacy practices.

- Support in analyzing texts for biases, perspectives, and power structures.

- Facilitating classroom activities that promote questioning, dialogue, and advocacy.

Multilingual Learner (ML) Literacy Support

- Coaching on translanguaging strategies and scaffolding for academic discourse.

- Integration of multilingual texts and dual-language formative assessments.

- Culturally and linguistically responsive instruction that values students’ full linguistic repertoires.

Equity-Centered Literacy for Students from Historically Marginalized Communities

- Professional learning on culturally sustaining pedagogies and critical text selection.

- Design of lessons that center identity, voice, and sociopolitical consciousness.

- Support in creating writing and discussion protocols that promote analysis, advocacy, and agency.

Data Analysis and Action Planning

- Analysis of literacy data to identify gaps and target interventions.

- Developing equity-driven action plans for literacy improvement.

- Facilitating collaborative data inquiry sessions for educators.

Inclusive Literacy for Students with Disabilities

- Support in applying Universal Design for Learning (UDL) principles to literacy.

- Tools and resources to differentiate access and expression, including visuals, guided discussions, and multimodal tools.

- Strategies for embedding metacognitive reflection, goal setting, and self-assessment.

Family and Community Literacy Engagement

- Parent and caregiver workshops on supporting literacy development at home.

- Community events centered on culturally responsive and critical literacy themes.

- Partnerships with local organizations to promote equity-focused literacy initiatives.

Systematic Phonemic Awareness and Phonics Support

- Implementation of phonemic awareness activities honoring linguistic diversity.

- Equity-focused phonics instruction with diverse and meaningful materials.

Fluency and Vocabulary Development Support

- Designing fluency-building activities, including performance tasks and peer feedback.

- Contextual vocabulary instruction embedded across disciplines.

Evidence-Based Writing Instruction Support

- Coaching teachers to integrate evidence-based writing practices into the curriculum.

- Empowering students to write about topics they care deeply about.

- Structuring writing tasks that connect to real-world advocacy and action.

Reading Comprehension Support

- Designing meaning-making and comprehension-building activities, including performance tasks and peer feedback.

- Contextual vocabulary instruction embedded across disciplines.

A Call to Action

Centering Critical Literacy

Critical literacy is the key to achieving justice and equity for all learners. It is more than a set of skills—it is a transformative practice that empowers students to question the world, challenge inequities, and advocate for meaningful change. To ignore the urgency of critical literacy is to accept the status quo, perpetuating barriers that silence voices and limit potential. “Critical literacy helps individuals question societal issues and norms relating to human relationships in speech and writing” (Jimola & Olaniyan, 2021). Critical literacy has the potential to be paradigm-shifting as it encourages students to interrogate and reflect on the social constructs that shape their understanding of the world, thereby enhancing their analytical skills.

This work requires more than ambition; it demands unwavering commitment. We must believe in the boundless potential of every learner and reimagine traditional approaches to literacy instruction. By centering critical literacy and building on its four pillars—questioning power, analyzing perspectives, challenging biases, and fostering agency—we create not only readers and writers but also changemakers.

This is how we create classrooms where every student feels seen, valued, and empowered to thrive.

The Core Collaborative Learning Network invites educators, leaders, and communities to take bold action. Together, let’s reimagine literacy as a pathway to justice—a way to break cycles of inequity and build opportunities for all. Join us in this life-changing work, and let’s create a future where critical literacy is the foundation of equity, empowerment, and lasting change.

Achieving literacy and justice for all is not an isolated endeavor. It flourishes when rooted in equity, nurtured through collective efficacy, and sustained by belonging and deliberate practice.

Are you ready to embark on a journey towards literacy excellence? Click here for additional information.

References

- Andrade, H., & Du, Y. (2007). Student responses to criteria-referenced self-assessment. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 32(2), 159-181. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602930600801928

- August, D., & Shanahan, T. (Eds.). (2006). Developing literacy in second-language learners: Report of the National Literacy Panel on Language-Minority Children and Youth. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Bialystok, E. (2007). Acquisition of literacy in bilingual children: A framework for research. Language Learning, 57(1), 45-77. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9922.2007.00412.x

- Bolduc, J. (2009). Effects of a music programme on kindergartners’ phonological awareness skills. International Journal of Music Education, 27(1), 37-47. https://doi.org/10.1177/0255761408099063

- Cutting, L. E., Materek, A., Cole, C. A., Levine, T. M., & Mahone, E. M. (2009). Effects of fluency, oral language, and executive function on reading comprehension performance. Annals of Dyslexia, 59(1), 34-54. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11881-009-0022-0

- Dunlosky, J., Rawson, K. A., Marsh, E. J., Nathan, M. J., & Willingham, D. T. (2013). Improving students’ learning with effective learning techniques: Promising directions from cognitive and educational psychology. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 14(1), 4-58. https://doi. org/10.1177/1529100612453266

- Dweck, C. S. (2006). Mindset: The new psychology of success. Random House.

- Earley, P. and Porritt, V. (2013). Evaluating the impact of professional development: the need for a student-focused approach. Professional Development in Education, 40(1), 112-129. https://doi.org /10.1080/19415257.2013.798741

- Ehri, L. C., Nunes, S. R., Willows, D. M., Schuster, B. V., Yaghoub-Zadeh, Z., & Shanahan, T. (2001). Phonemic awareness instruction helps children learn to read: Evidence from the National Reading Panel’s meta-analysis. Reading Research Quarterly, 36(3), 250-287. https://doi. org/10.1598/RRQ.36.3.2

- Flint, A. S. (2022). “See, that’s me. I’m proud”: Manifestations of a humanizing and culturally sustaining writing pedagogy for young writers. Language Arts, 100(2), 83–95.

- García, O., & Wei, L. (2014). Translanguaging: Language, bilingualism and education. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Graham, S., & Sandmel, K. (2011). The process writing approach: A meta-analysis. The Journal of Educational Research, 104(6), 396-407. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220671.2010.488703

- Guskey, T. R. (2018). On your mark: Challenging the conventions of grading and reporting. Solution Tree Press.

- Hattie, J. (2009). Visible learning: A synthesis of over 800 meta-analyses relating to achievement. Routledge.

- IIbrahim, S. (2023). Using critical literacy approach for developing some efl persuasive writing skills among student teachers at faculty of education. , 34(133), 1-26. https://doi. org/10.21608/jfeb.2023.314121

- Jimola, F. E. and Olaniyan, A. S. (2021). Conceptualisation of critical literacy and argumentative writing as an essential tool for the development of dialectic reasoning among students. Interdisciplinary Journal of Sociality Studies, 1, 8-15. https://doi.org/10.51986/ijss-2021.vol1.02

- Kellner, D. and Share, J. (2005). Toward critical media literacy: core concepts, debates, organizations, and policy. Discourse Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education, 26(3), 369-386. https://doi. org/10.1080/01596300500200169

- Khor, C. P., Low, H. M., & Lee, L. W. (2014). Relationship between oral reading fluency and reading comprehension among esl students. GEMA Online Journal of Language Studies, 14(03), 19-32. https://doi.org/10.17576/gema-2014-1403-02

- Kühn, M., Schwanenflugel, P. J., & Meisinger, E. B. (2010). Aligning theory and assessment of reading fluency: automaticity, prosody, and definitions of fluency. Reading Research Quarterly, 45(2), 230-251. https://doi.org/10.1598/rrq.45.2.4

- Ladson-Billings, G. (1995). Toward a theory of culturally relevant pedagogy. American Educational Research Journal, 32(3), 465–491.

- Ladson-Billings, G. (2014). Culturally relevant pedagogy 2.0: a.k.a. the remix. Harvard Educational Review, 84(1), 74-84. https://doi.org/10.17763/haer.84.1.p2rj131485484751

- Moon, A., Stanford, C., Cole, R. S., & Towns, M. H. (2017). Decentering: a characteristic of effective student–student discourse in inquiry-oriented physical chemistry classrooms. Journal of Chemical Education, 94(7), 829-836. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jchemed.6b00856

- Muhammad, G. (2020). Cultivating genius: An equity framework for culturally and historically responsive literacy. Scholastic.

- Nicol, D. and Macfarlane-Dick, D. (2006). Formative assessment and self-regulated learning: a model and seven principles of good feedback practice. Studies in Higher Education, 31(2), 199- 218. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070600572090

- Panadero, E., & Alonso-Tapia, J. (2013). Self-assessment: Theoretical and practical connotations. When it happens, how is it acquired and what to do to develop it in our students. Electronic Journal of Research in Educational Psychology, 11(2), 551-576. https://doi.org/10.14204/ ejrep.30.12200

- Peachey, K. B. and Lee, C. C. (2023). Writing to grieve: solidarity in times of loss in educational community spaces. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 67(3), 136-149. https://doi.org/10.1002/ jaal.1313

- Perfetti, C., & Stafura, J. (2014). Word knowledge in a theory of reading comprehension. Scientific Studies of Reading, 18(1), 22-37. https://doi.org/10.1080/10888438.2013.827687

- RAND Reading Study Group. (2002). Reading for understanding: Toward an R&D program in reading comprehension. RAND Corporation.

- Rumelhart, D. E. (1980). Schemata: The building blocks of cognition. In R. J. Spiro, B. C. Bruce, & W. F. Brewer (Eds.), Theoretical issues in reading comprehension (pp. 33-58). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Sari, S. and Saadah, H. (2022). The learning impact of the online formative assessment system (ofas) for undergraduate medical students. ACTA Medical Health Sciences, (Volume 1 No 2), 71-78. https://doi.org/10.35990/amhs.v1n2.p71-78

- Schurz, M., Radua, J., Aichhorn, M., Richlan, F., & Perner, J. (2014). Fractionating theory of mind: A meta-analysis of functional brain imaging studies. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 42, 9-34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2014.01.009

- Shanahan, T., & Duke, N. K. (2012). Helping students meet the Common Core standards for reading. Reading Teacher, 66(3), 171–180.

- Shepard, L. A., Penuel, W. R., & Pellegrino, J. W. (2018). Using learning and motivation theories to coherently link formative assessment, grading practices, and large-scale assessment. Educational Measurement: Issues and Practice, 37(1), 21-34. https://doi.org/10.1111/emip.12189

- Topping, K. J. (2009). Peer assessment. Theory Into Practice, 48(1), 20-27. https://doi.org/10.1080/00405840802577569

- Vasquez, V. (2017). Critical literacy. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190264093.013.20

- Verhoeven, L. and Leeuwe, J. v. (2011). The simple view of second language reading throughout the primary grades. Reading and Writing, 25(8), 1805-1818. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-011-9346-3

- Westby, C. (2018). Learning academic vocabulary in first through third grade. Word of Mouth, 30(1), 5-8. https://doi.org/10.1177/1048395018796520a

- Wiliam, D. (2011). Embedded formative assessment. Solution Tree Press.

- Zelazo, P. D., Müller, U., Frye, D., & Marcovitch, S. (2003). The development of executive function in early childhood. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 68(3), vii-137. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0037-976X.2003.00261.x