Let Down by Grades: A Personal Anecdote

I was one of those students who came out of high school with great marks, especially in mathematics and sciences. So I was really surprised when I struggled mightily in my first year of university when I was required to apply and extend my knowledge and skills. This was especially the case in problem-based learning opportunities – but I also experienced it with written exams where I had typically performed very well. While grappling with yet another failed midterm result in one class, I remember thinking, “I had good grades, why isn’t this easy for me?”

My question revealed the firm belief that I held as a student: Good grades predict future success. How many students (and parents, guardians, and teachers!) still subscribe to that belief?

What is the Purpose?

Debating the purposes and utility of grading can make for a controversial discussion. There are often fundamental differences in beliefs or assumptions about the role and usefulness of grades in a student’s life. However, since the expectation that students are issued grades at the end of a unit or course of study is unlikely to go away any time soon – it is part of the ‘grammar of schooling’ – and keeping them helps maintain the public’s trust in the system, examining the beliefs that underpin grading systems and the faith people have in them are worth significant reflection and discussion by school and system leaders.

What I didn’t know as a high school student is how grades are determined is only the visible “tip of the iceberg” of student assessment and evaluation practices. Further, they flow from the practices that direct how units and lessons are planned, how assignments are crafted, and how feedback is provided to students along the way.

Ultimately, these are the practices that help students become self-empowered learners who can feel confident and ready to face their futures, not the grade that appears on the report card.

A Competency-Based Model for More Accurate Communication

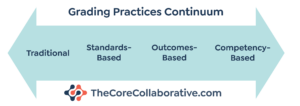

However, grading practices can signal whether students are authentically equipped with the knowledge, skills and – ultimately – competencies to successfully navigate their futures across a variety of contexts. They exist along a continuum:

Click here to view or download full grading practices continuum

The further a school or system moves along to the right side of this continuum, the more likely the grades produced and reported will be able to help students (and their parents/guardians) feel more confident of future success in whatever pathway that a student chooses to follow.

School and system leaders need to examine whether their grading practices align with the assessment and evaluation practices used in classrooms in both directions:

- From the System (‘big picture’): Do the grading practices (and expectations or structures) dissuade teachers from using formative-, self-, and summative assessment practices that facilitate developing competency rather than superficial or short-term knowledge?

- From the Classroom (specific): Do the grading practices (and expectations or structures) allow for descriptive feedback about learning to be reported effectively to students, parents/guardians, and to system leaders?

If we want to develop systems that prepare students to become self-empowered learners who are, themselves, confident in their abilities to deal with what the future may bring (and we want to ensure their parents and guardians know this, too) we best start by discussing and assessing the grading systems we are using in our schools and how they may be driving the effective or ineffective practices in classrooms.