What if we stopped asking what students learned and started asking who they became in the process?

That’s the transformative vision behind L. Dee Fink’s Taxonomy of Significant Learning (2003). Fink’s framework invites us to move beyond the narrow definition of academic success and reimagine learning as a deeply human process—intellectual, emotional, social, and reflective.

While most educators are familiar with Bloom’s Taxonomy, Fink believed something was missing. Too often, learning was reduced to levels of cognitive recall, devoid of identity, empathy, or purpose. Fink wanted to expand the conversation to give educators a way to design learning that matters and that lasts. Learning that changes not just what students can do, but who they are becoming.

Who Was L. Dee Fink and Why Did He Create This Taxonomy?

Who Was L. Dee Fink and Why Did He Create This Taxonomy?

L. Dee Fink was a respected educator and scholar who spent his career helping college faculty create more meaningful learning experiences. As Director of the Instructional Development Program at the University of Oklahoma, he observed countless classrooms and partnered with faculty across disciplines. What he saw was a need for a more integrated and humanizing approach to course design.

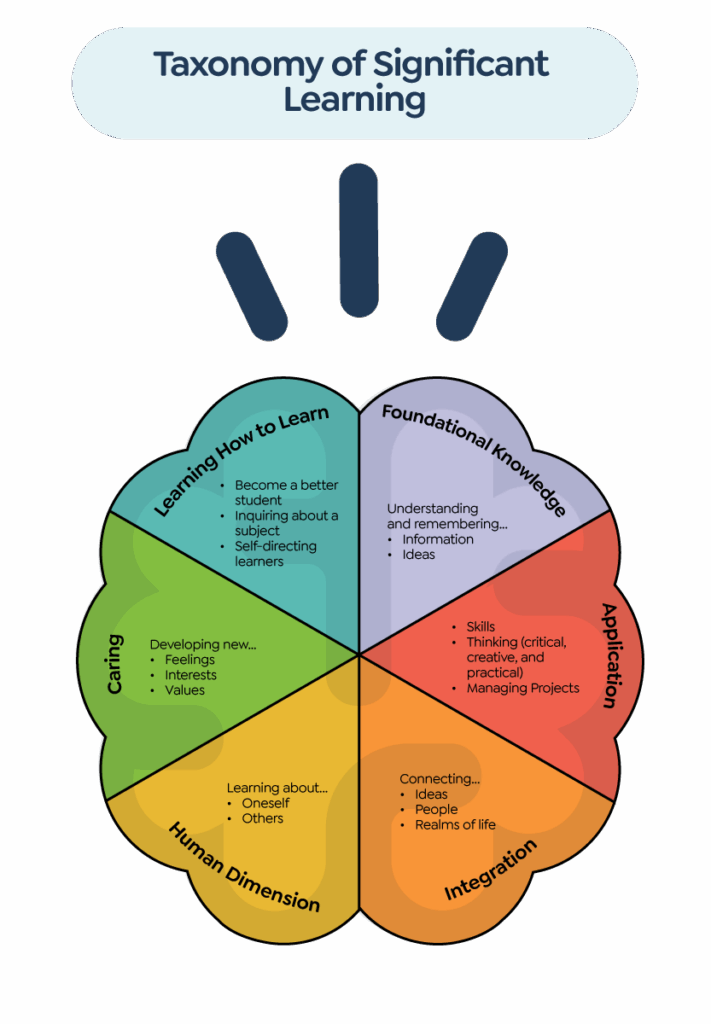

In response, he developed the Taxonomy of Significant Learning, introduced in his landmark 2003 book Creating Significant Learning Experiences. This taxonomy offered six interdependent types of learning:

- Foundational Knowledge

- Application

- Integration

- Human Dimension

- Caring

- Learning How to Learn

These dimensions weren’t meant to be taught in isolation. They were designed to work together, to reinforce and deepen one another, so that students experience learning that is not only retained, but transformative. Fink’s model doesn’t just prepare students for tests; it prepares them for life.

In our forthcoming book Metacognitive Clarity, we embrace this vision and build upon it. We help learners become more aware of how they think, why they feel, and how they grow—so that learning becomes a conscious, empowering act. In Leading Impact Teams, we take this same vision to the team level, showing how teachers and students can engage in shared, reflective inquiry that places the learner at the center (Bloomberg & Pitchford, 2024).

Foundational Knowledge: Building the Bricks of Meaning

At the core of any subject is foundational knowledge: ideas, facts, and concepts. However, stopping there limits learning to surface-level understanding. Fink reminds us that foundational knowledge is only meaningful when it becomes the base for deeper reflection and use (Fink, 2003).

In Metacognitive Clarity, we support students in asking reflective questions that push beyond memorization:

What do I understand so far, and where do I need more clarity?

Through self-assessment, guided feedback, and dialogue with peers, learners become more aware of their strengths and gaps and better equipped to navigate complex content with confidence and purpose.

Application: Turning Knowing into Doing

Foundational knowledge becomes powerful when it’s applied. In this domain, students engage in critical, creative, and practical thinking, developing skills and managing real tasks. Fink describes this as a shift from “knowing” to “doing” (2003).

In Leading Impact Teams, teachers and students co-construct success criteria and engage in cycles of feedback and deliberate practice (Bloomberg & Pitchford, 2017). This builds metacognitive stamina in which learners learn to monitor their approach, reflect on their process, and make thoughtful adjustments.

Clarity Cue:

What strategy am I using and how is it helping me meet my goal?

Integration: Connecting the Dots Across Contexts

Application sets the stage for integration—linking ideas across disciplines, connecting learning to real-life situations, and seeing patterns that lead to insight. Fink saw integration as a vital bridge between academic learning and personal meaning (2003).

This resonates deeply with our work. When students are encouraged to make connections between what they’re learning and who they are, learning becomes relevant—and retention deepens. Within Impact Teams, integration often shows up in collaborative lesson design and student-led reflection routines that link learning goals to real-world purpose.

Connection Question:

How does this connect to something I already know or something I care about?

Human Dimension: Knowing Self and Others

Learning doesn’t happen in a vacuum. It happens in the context of identity, community, and relationship. Fink called this the human dimension, where students come to better understand themselves and others (2003).

This is foundational to metacognitive clarity. When students reflect on their values, culture, and identity, they gain clarity not only about their learning but also about their place in the learning process. Impact Teams support this through learner-centered inquiry, creating classrooms where voice, choice, and perspective are honored (Bloomberg & Pitchford, 2017).

Equity Anchor:

How does my identity shape how I learn and how might others experience this differently?

Caring: Learning That Sparks Passion and Purpose

Fink challenges educators to design learning that cultivates new interests, values, and commitments. When students care, they engage more deeply and persist through difficulty. Caring creates the emotional investment that turns compliance into ownership (Fink, 2003).

In Metacognitive Clarity, we emphasize purpose-driven goal setting. Students are encouraged to ask:

Why does this learning matter to me and how might I use it to make a difference?

When students see how their learning connects to something bigger than themselves, they’re more likely to invest their time and energy not for a grade, but for growth.

Learning How to Learn: The Metacognitive Engine

The final domain, learning how to learn, is the heartbeat of our book. Fink describes it as developing the ability to be a self-directed, reflective learner (2003). It’s not just about learning content; it’s about learning how to navigate future learning.

Through routines like goal setting, self-assessment, and feedback tracking, learners begin to internalize the skills of lifelong learning. In Impact Teams, educators create the conditions for these routines to become habits of mind and heart (Bloomberg & Pitchford, 2017).

Metacognitive Cue:

What helps me learn best and how will I use that insight next time?

Designing for Significance

What makes Fink’s model so powerful is its interactive nature. These domains are not meant to be tackled one at a time. They are deeply connected, reinforcing and amplifying each other.

In our work with educators across the country, we’ve seen how Impact Teams can become engines for this kind of significant learning. When educators engage in collaborative inquiry and when students are partners in that process, metacognitive clarity becomes more than a practice—it becomes a culture.

In a world that demands not only knowledge, but clarity, compassion, and agency, this is the kind of learning our students deserve.

Join the Impact Team Movement to bring this work to life in your school(s)!

Coming Fall 2025

Don’t miss our new book, Metacognitive Clarity: Think Rigorously. Advance Democracy., by Paul J. Bloomberg, Isaac Wells, and St. Claire Adriaan. Published by Mimi and Todd Press.

References

- Fink, L. D. (2003). Creating Significant Learning Experiences: An Integrated Approach to Designing College Courses. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Bloomberg, P. J., & Pitchford, B. (2017). Leading Impact Teams: Building a Culture of Efficacy and Agency. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin.