Do you find yourself wondering, “How will my students get better at this?” or “What pathway will help them accomplish their goals?”

Are you worried that students are not getting enough practice or that the practice doesn’t seem to be having an impact?

Have you ever had students moan or complain “Why do we have to do this again?”

From my experience, these thoughts and concerns are common. We know students need considerable practice with certain skills and concepts but are not always sure how to make this happen. This quick read attempts to make the case that there are many ways to engage students in practicing success criteria without the boredom and dread that can sometimes accompany repetition.

The Power of Repetition

Repeating the same or similar tasks increases opportunities for students to deepen and apply what they know without the need for new instructions and guidelines. Students need to understand tasks completely to focus on the skills and content knowledge they are gathering and using. The predictability of transferable tasks reduces cognitive load and frees up valuable working memory so learners can focus on the skills and concepts the task is meant to develop. Even when the task changes, the success criteria, and clear expectations of what a product or performance should look like, sound like, etc., can remain the same.

Connecting with Tasks

Connecting with Tasks

Cognitive neuroscientist and educational psychologist Mary Helen Immordino-Yang and Harvard doctoral candidate Matthias Faeth claim that “the learner’s emotional reaction to the outcome of his efforts… shapes his future behavior.” (Sousa, 2010) They were writing about efficacy, a person’s belief, based on experiences, regarding their ability to accomplish a task or achieve a goal. However, my work in education over the past couple of decades has convinced me that we can expand this thinking to specific tasks. Everyone’s time and energy are limited; when learners feel connected to and understand the relevance of a task, they are much more likely to dedicate their full attention and effort.

Engaging Practice

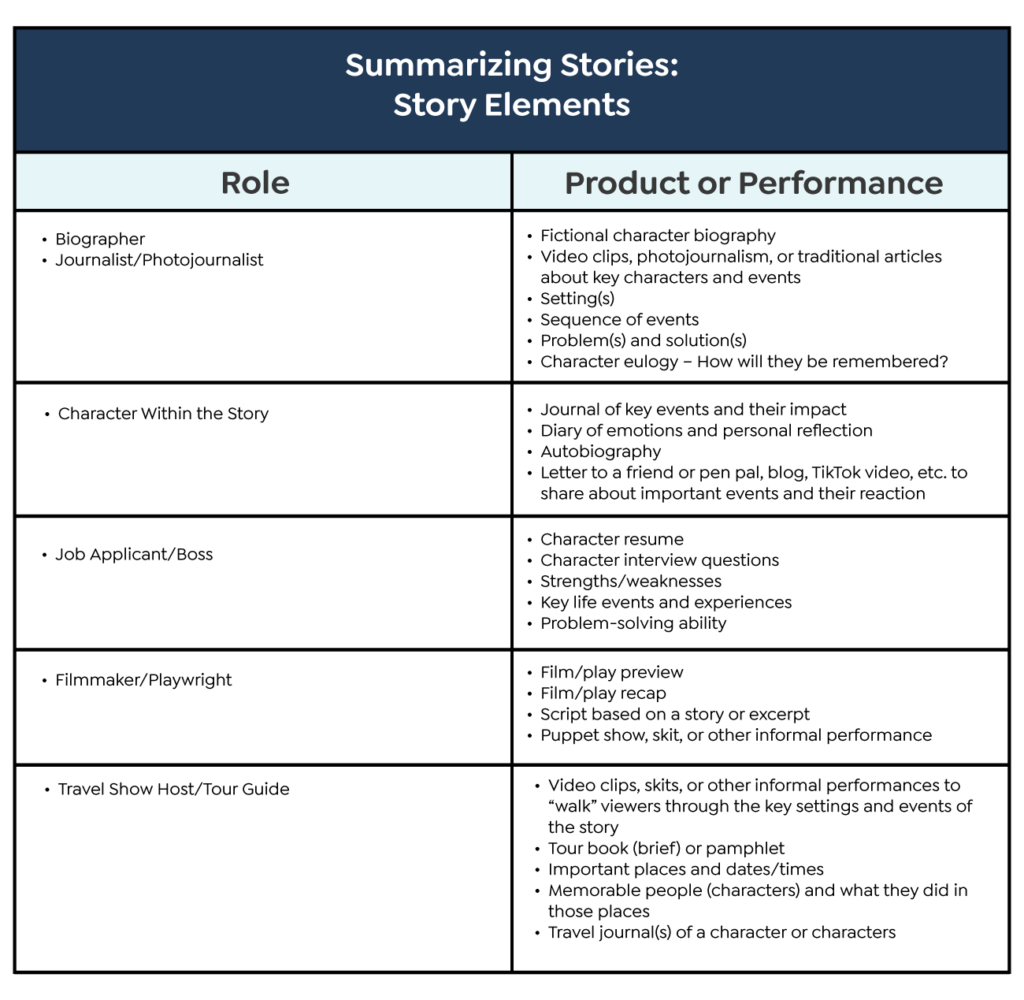

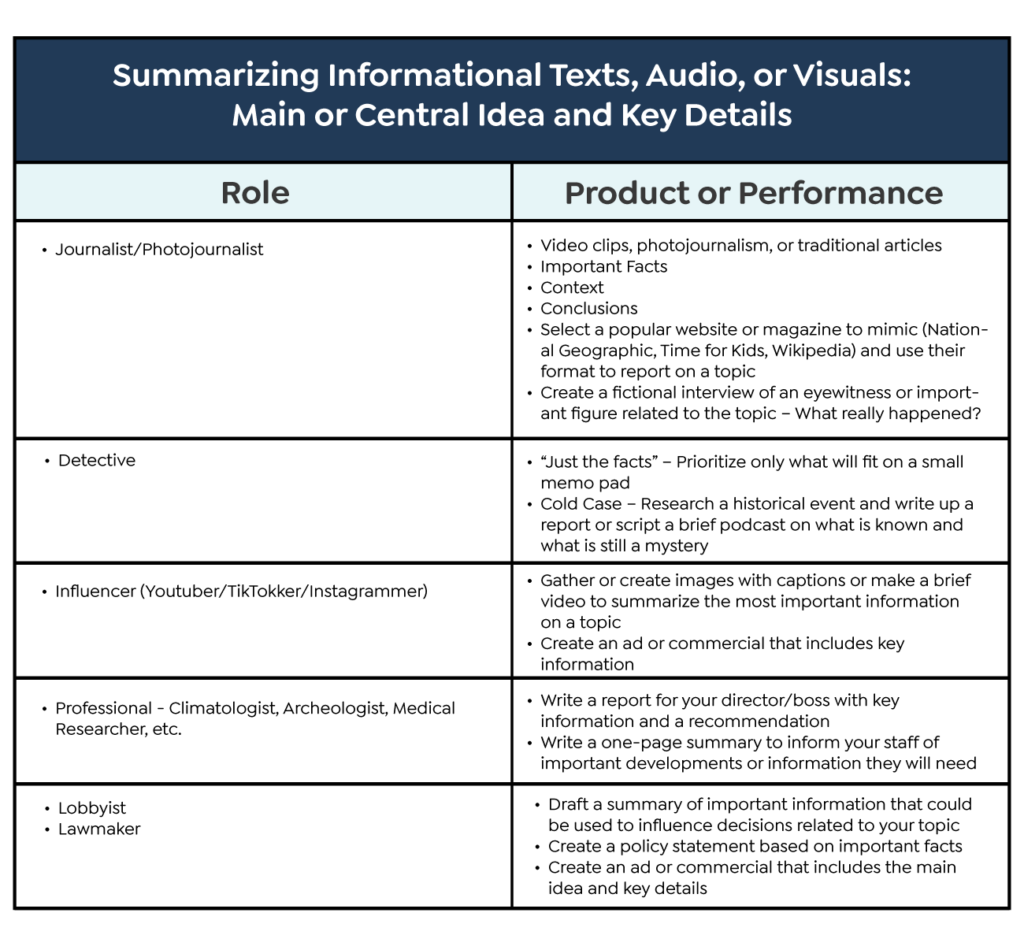

With this in mind, we can consider a variety of tasks that will demonstrate learners’ understanding and skills but allow for creativity and originality. The R.A.F.T. writing strategy, which has authors focus on Role, Audience, Format, and Topic (Santa, Havens, and Valdes, 2004) as they write, is an effective way of planning innovative ways for students to show their learning. In the chart below, I have summarized these components as the role learners will take on and the product or performance created.

Applications with Summarizing

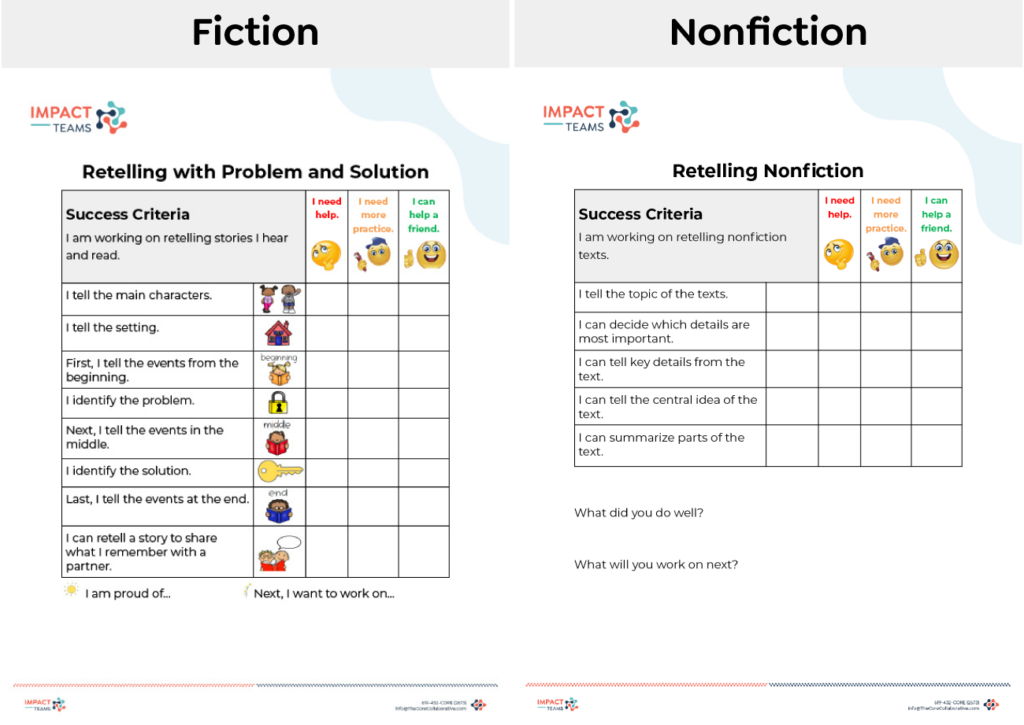

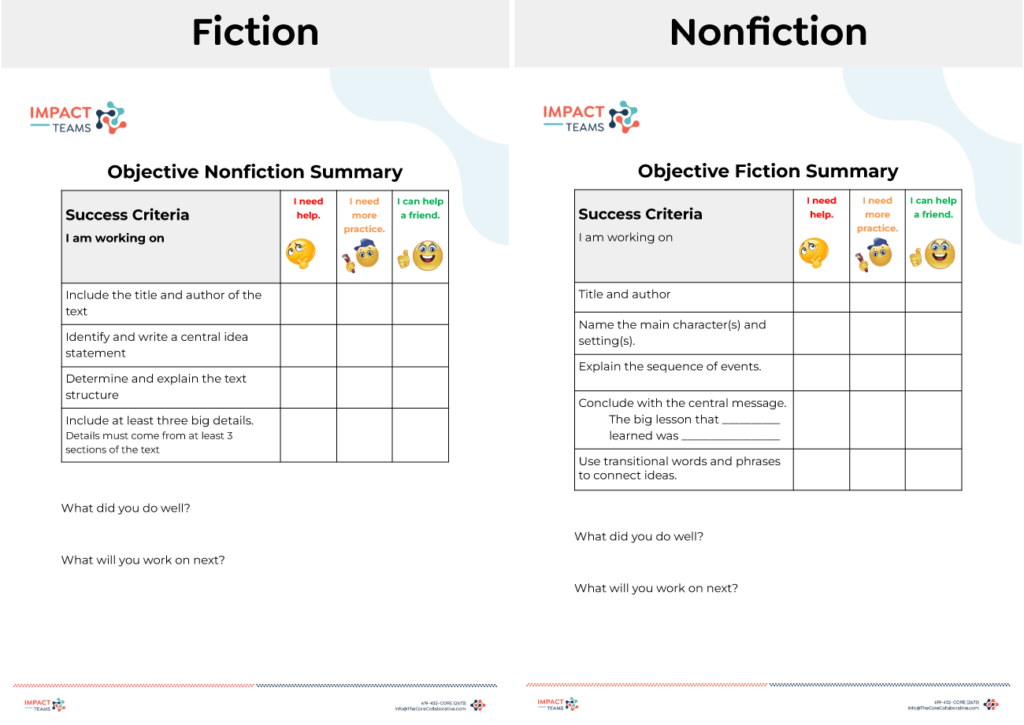

The skill of summarizing, which begins as retelling in the early grades, is an essential skill for all learners and enables students to engage in deeper thinking and analysis of the stories and information they read, listen to, and view. The checklists below represent possible success criteria for summarizing across a few grade levels.

Students need countless opportunities to practice meeting the success criteria above, but that doesn’t mean they can’t have fun practicing. The lists below are by no means exhaustive but are intended to get you thinking. Take some time to discuss with your students and your colleagues

Students need countless opportunities to practice meeting the success criteria above, but that doesn’t mean they can’t have fun practicing. The lists below are by no means exhaustive but are intended to get you thinking. Take some time to discuss with your students and your colleagues  which roles and tasks might be best for their next learning experiences.

which roles and tasks might be best for their next learning experiences.

Reflect:

- How are you already building interest and engaging students in their practice?

- What would you change or improve about the examples provided?

- How can you adapt these ideas and examples to your class or school?

Download a PDF of the Show What You Know samples.

Santa, C., Havens, L., & Valdes, B. (2004). Project CRISS: Creating Independence through Student-owned Strategies. Dubuque, IA: Kendall Hunt.

Sousa, D. A. (2010). Mind, brain, and education: Neuroscience implications for the classroom. Solution Tree Press.