Universal Design for Learning (UDL) has always asked educators to begin with a powerful question: How can we design instruction that honors learner variability from the start? The framework, first articulated by David Rose and Anne Meyer at CAST in the 1990s, challenges us to remove barriers and provide multiple pathways so that every student can thrive. Their seminal text, Teaching Every Student in the Digital Age (1998), and later Universal Design for Learning: Theory and Practice (Meyer, Rose, & Gordon, 2014), laid the foundation for what has become a global movement for equity in learning.

More recently, leaders like Katie Novak have amplified UDL as a framework for equity, accessibility, and inclusion—and now, as a lens for thinking about how we responsibly use AI in education. As Andratesha Fritzgerald reminds us in Antiracism and UDL (2020), the framework is not just about choice and flexibility, but about justice and liberation for every learner.

But here’s the tension: teachers already carry an enormous load. Analyzing multiple sources of evidence—formative assessments, exit tickets, student reflections, performance tasks, even family input—can feel overwhelming. Enter AI.

What Katie Novak Says

Novak has been clear: AI is not about replacing teachers, it’s about amplifying their impact. In her words, “Embracing AI is the ultimate power move in education.” She highlights that when AI is used through the lens of UDL, it can:

- Help teachers design flexible options for how students access content and show understanding.

- Lighten the planning load, allowing more time for relationships and feedback.

- Provide scaffolds that help teachers refine instruction for equity and accessibility.

Her review of LUDIA, an AI tool designed with UDL in mind, shows how AI can support the design of diverse learning experiences—but also how critical it is that educators stay in the driver’s seat.

Defining UDL in Practice

At its core, Universal Design for Learning (UDL) is a framework for proactively designing instruction to reduce barriers and ensure access for all learners. In practice, this means:

- Multiple Means of Representation: Presenting information in different ways (text, visuals, audio, hands-on experiences).

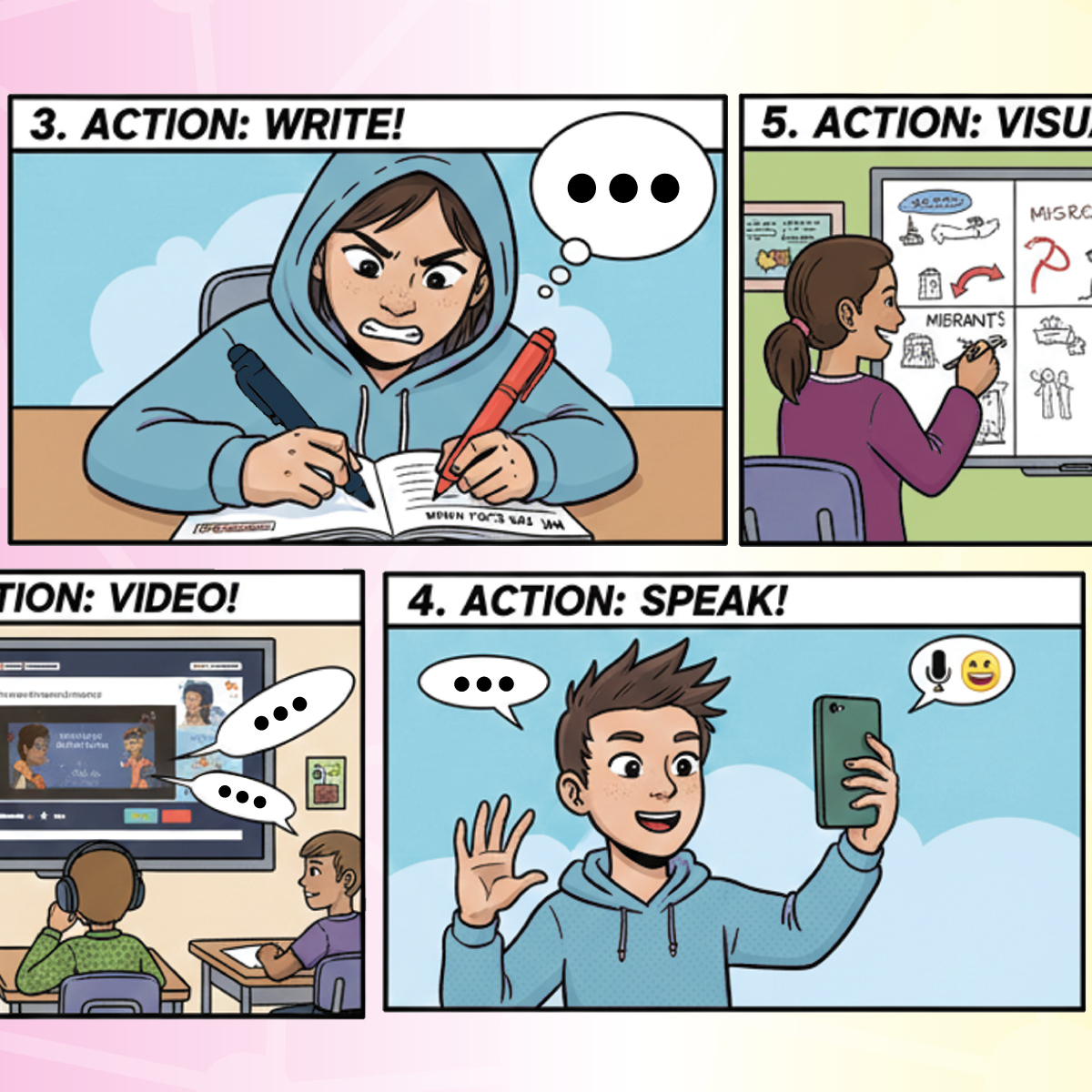

- Multiple Means of Action & Expression: Allowing students to show what they know through varied formats (writing, speaking, drawing, creating media).

- Multiple Means of Engagement: Offering choices and culturally responsive strategies to sustain motivation and interest.

UDL is not about making learning easier—it is about making it accessible and rigorous for every student.

Classroom Example: A middle school social studies teacher is introducing a unit on migration. She shares a text article (representation through reading), a short documentary clip (representation through video), and an interactive map (representation through visuals). Students then choose how to demonstrate initial understanding: writing a paragraph, recording a brief Flip video reflection, or sketching a storyboard of a migrant’s journey (action & expression). To sustain engagement, she connects the unit to students’ own family histories, inviting them to bring in a story or artifact from home. The rigor of the content remains high, but every student has multiple entry points and authentic ways to show learning.

A Brief Timeline of UDL’s Evolution

- Early 1990s – CAST Origins: David Rose and Anne Meyer begin applying principles of universal design in architecture to education, laying the groundwork for UDL.

- 1998 – First Major Publication: Rose & Meyer publish Teaching Every Student in the Digital Age, defining UDL’s three principles: representation, action & expression, and engagement.

- 2000s – Policy Uptake: UDL gains traction in U.S. policy, cited in the Higher Education Opportunity Act of 2008 as a framework for inclusive curriculum design.

- 2010s – Global Expansion: Universal Design for Learning: Theory and Practice (Meyer, Rose, & Gordon, 2014) cements UDL as a global equity framework, adopted across Canada, Europe, and Australia.

- 2020s – Justice and AI Integration: Researchers like Andratesha Fritzgerald connect UDL to antiracism and justice, while Katie Novak and others explore how AI can amplify UDL’s promise in schools.

Connecting to Evidence-Based Practice

In our forthcoming book, AI-Powered PLC Protocols (Bloomberg, 2025), we argue that analyzing evidence is the beating heart of professional learning. Evidence is not limited to numbers on a screen—it includes student work, anecdotal notes, student interviews, self-assessments, peer reflections, performance tasks, and even community and family feedback.

AI can help educators triangulate this wide range of evidence without losing sight of equity and humanity. Here’s how:

- Organizing evidence: AI can cluster student responses (written, oral, digital) into themes aligned with success criteria.

- Spotting strengths and barriers: Instead of only flagging deficits, AI can highlight patterns of brilliance across learners, reinforcing an asset-based approach.

- Cross-referencing modalities: UDL reminds us that evidence comes in multiple forms. AI can surface insights across text, audio, visual, and performance artifacts, helping teams see connections they might otherwise miss.

- Supporting differentiation: By aligning patterns to surface, deep, and transfer strategies, AI can suggest instructional moves that respect learner variability.

Teacher-Facing Scenarios

Elementary Example – Reading Fluency

A 3rd-grade teacher collects oral reading samples. Using AI, she receives clusters that show where students stumble (decoding vs. prosody vs. comprehension). AI then links these findings to UDL-aligned strategies: offering audio models, fluency practice through performance, and comprehension checks with visuals. The teacher uses this evidence to differentiate guided reading groups while students self-assess using progress trackers. Importantly, students still engage in on-demand oral and written fluency checks to demonstrate authentic growth.

Middle School Example – Science Labs

In a 7th-grade lab, students submit digital lab notes, photos, and self-reflections. AI synthesizes patterns: some students excel at data collection but struggle to explain cause-and-effect. The teacher uses this analysis to provide choice: graphic organizers for some, simulation extensions for others, and peer explanation routines. Students then engage in metacognitive reflection: Which strategy helped me explain my thinking most clearly? While AI supports scaffolds, students are still required to present findings orally and submit written explanations to build mastery in core skills.

High School Example – Civic Writing

In an 11th-grade civics class, students draft position papers. AI highlights strengths in evidence use but gaps in counterarguments. The teacher shares these patterns in a class discussion, inviting students to co-construct success criteria for effective argumentation. Learners choose supports: sentence starters, mentor texts, or debate prep. The process models democracy in action—students shaping the standards by which they’ll be assessed. Still, students must complete on-demand argumentative writing and live debates, ensuring they build authentic proficiency in speaking and writing alongside AI-supported practice.

| What Students Are Doing | What AI Provides | What the PLC Is Doing (After AI Analysis) | UDL Lens + Specific Examples | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Completing oral, written, and digital performance tasks aligned to UDL success criteria | First-pass clustering of evidence (strengths, barriers, patterns across groups) | Validating accuracy of AI groupings; checking if patterns match classroom reality | Multiple Means of Action & Expression: e.g., 8th graders submit a lab report (written), a narrated slide deck (oral + visual), or a recorded screencast (digital). PLC ensures all products align to the same success criteria. | |||||

| Engaging in self-assessments, reflections, and peer feedback | Drafted summaries of common strengths/misconceptions | Triangulating AI insights with benchmarks, teacher notes, family input | Multiple Means of Engagement: e.g., students set goals in different ways — a reflection journal (writing), a Flip video log (oral), or a checklist with icons (visual). PLC ensures choice is meaningful, not optional fluff. | |||||

| Practicing metacognitive strategies: self-questioning, goal-setting, tracking growth | Suggested instructional moves (surface, deep, transfer) connected to UDL | Ensuring suggested moves align with rigor, equity, and grade-level standards | Multiple Means of Representation: e.g., AI surfaces that many students misinterpret a graph. PLC chooses to reteach with multiple models — a hands-on simulation, a video explanation, and a text-based walkthrough — so all learners can access the concept. | |||||

| Participating in oral presentations and on-demand writing to demonstrate mastery | Options for scaffolds (sentence starters, exemplars, practice routines) | Deciding which scaffolds preserve rigor while supporting diverse learners | Balancing scaffolds + rigor: e.g., AI suggests sentence frames for debate prep. PLC ensures students still must complete a live debate and an on-demand argumentative essay without AI support to demonstrate authentic mastery. | |||||

| Using tech tools responsibly to practice skills | Quick visualization of progress (charts, trends, progress toward success criteria) | Discussing as a PLC how to differentiate next steps, monitor progress, and maintain mastery expectations | Barrier removal: e.g., AI generates visuals of reading fluency progress. PLC ensures students with dyslexia have access to text-to-speech for practice, but also require oral fluency checks to build mastery. |

Democracy, Metacognition, and UDL

In our other forthcoming book, Metacognitive Clarity: Think Rigorously. Advance Democracy. (Bloomberg, Wells, & Adriaan, 2025), we argue that metacognition is not just a learning strategy—it is a democratic practice. When learners think about their own thinking, they build the clarity, courage, and agency required to participate fully in democratic life.

This is where UDL, AI, and evidence analysis intersect:

- UDL ensures access to learning for every student (Rose & Meyer, 1998; Meyer, Rose, & Gordon, 2014).

- AI accelerates our ability to analyze evidence across diverse learners (Novak, 2023).

- Metacognition equips students with the tools to reflect, self-assess, and take ownership of their learning (Bloomberg, Wells, & Adriaan, 2025).

- Democracy emerges when students and teachers engage together in reflective, evidence-driven decisions that honor every voice (Fritzgerald, 2020; Hehir, 2016).

Mitigating AI: Preserving Rigor in Core Skills

Katie Novak and UDL principles make it clear: AI must be used intentionally, not as a shortcut. Students can and should use tech tools to rehearse, scaffold, and refine their learning. But rigor requires that they still demonstrate on-demand writing, oral presentations, and authentic performance tasks without AI support. These moments are where mastery in speaking and writing is built.

AI becomes the assistant, not the replacement. It helps learners get feedback, practice metacognition, and choose strategies—but the work of thinking, writing, and speaking remains in their hands. This balance preserves equity, rigor, and agency.

If UDL is about removing barriers, and evidence analysis is about knowing where to act, then AI becomes the bridge. It helps teachers quickly make sense of the complexity before them and respond in ways that are precise, inclusive, and humane.

And this is where democracy and metacognition converge: classrooms become spaces where evidence is examined together, where every learner’s voice is honored, and where reflective practice builds both academic mastery and civic capacity. In this way, AI + UDL is not just about efficiency or accessibility — it is about preparing learners to participate fully in a democratic society.

Join the Impact Team Movement and power your PLC protocols with AI!

References

- Bloomberg, P. (2025). AI-powered PLC protocols: Brains + bots = Freeing teachers to do what matters most [Manuscript in preparation]. Mimi & Todd Press.

- Bloomberg, P., Wells, I., & Adriaan, S. C. (2025). Metacognitive clarity: Think rigorously. Advance democracy. Mimi & Todd Press.

- Fritzgerald, A. (2020). Antiracism and universal design for learning: Building expressways to success. CAST.

- Hehir, T. (2016). Effective inclusive schools: Designing successful schoolwide programs. Jossey-Bass.

- Meyer, A., Rose, D. H., & Gordon, D. (2014). Universal design for learning: Theory and practice. CAST.

- Novak, K. (2022, March 10). Why UDL is the solution to bridging the digital divide in education. Novak Education.

- Novak, K. (2023, June 20). The future of learning: UDL, tech, and AI in the classroom. Novak Education.

- Novak, K. (2023, August 14). Why embracing AI is the ultimate power move in education. Novak Education.

- Novak, K. (2024, February 6). AI for UDL: A review of the AI tool LUDIA. Novak Education.

- Rose, D. H., & Meyer, A. (1998). Teaching every student in the digital age: Universal design for learning. ASCD.